We're not Getting Dumber

It's Wikipedia all over again

I've seen a lot of conversation lately about people getting dumber because of LLM usage. Studies and research papers documenting the loss of executive function, critical thinking, and memory, thanks to people offshoring their brain power to LLM agents.

My gut instinct was to compare this to the time when teachers would tell you not to use Wikipedia for your assignments because it took away from your research skills, or even before that, them telling you not to use a calculator.

But, I still want to give credence to this argument, in case it actually does bear some truth. After doing my due diligence and reading the papers, though, I've got some qualms with the methodology. Specifically, I don't agree with the way they're measuring our "intelligence."

Let’s get this out the way from the get-go: I do take these concerns seriously (who wouldn’t?). The impact of new technologies on our minds is significant and deserves attention. However, the current approach to reporting this issue looks to me more like media-chasing rather than actual research.

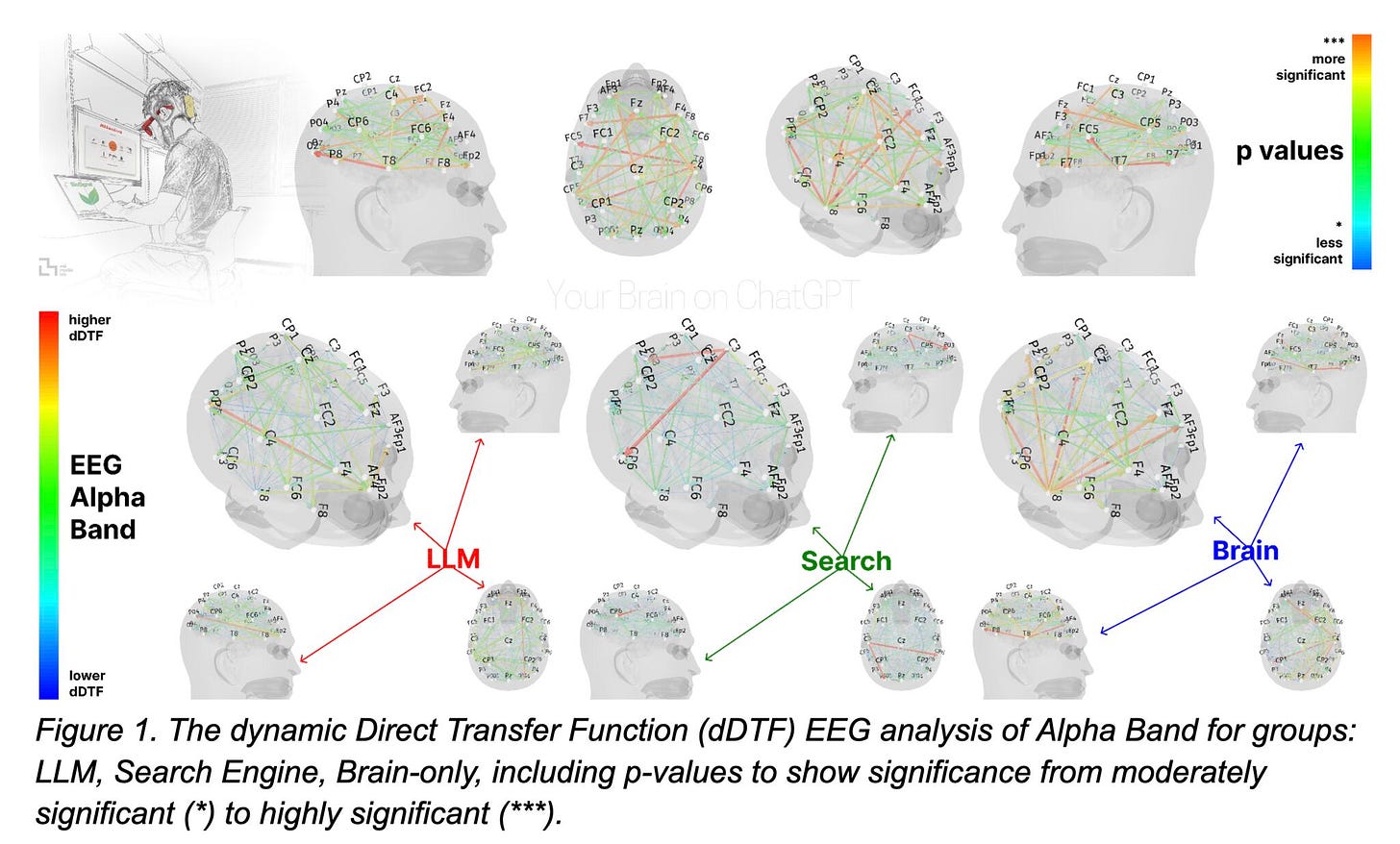

The paper "Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt when Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task" by Nataliya Kosmyna, Eugene Hauptmann, et al., that's been doing the rounds on LinkedIn and Twitter as of late, does outline some measured decrease in mental faculties in students.

The researchers found that "EEG revealed significant differences in brain connectivity: Brain-only participants exhibited the strongest, most distributed networks; Search Engine users showed moderate engagement; and LLM users displayed the weakest connectivity." They also noted that "cognitive activity scaled down in relation to external tool use."

But.

That's only because they're measuring the repeated performance over writing a single essay: once aided by AI, once aided by Google, once by themselves, and (optionally) once again using AI after having done it themselves. The study tracked 54 participants over four months, with researchers concluding that "LLM users consistently underperformed at neural, linguistic, and behavioral levels."

Yeah, that’s one hell of a headline.

Now, keeping in mind that their sample size is only 54 people in the same area, which is in itself troublesome for a paper that's being cited as absolute truth.

This methodology seems to be missing some crucial context:

First, all of these people were born into the internet era, which means their brains have already been exposed to other, arguably more impactful cognitive influences like social media, the never-ending stress of a 24-hour news cycle, and the lack of places for actual mental stimulation (the often-called third spaces).

Most importantly, Second, people's performance under a single menial task isn't reflective of their mental faculties as a whole.

The study also found that "self-reported ownership of essays was the lowest in the LLM group and the highest in the Brain-only group" and that "LLM users also struggled to accurately quote their own work."

While these findings would be interesting once expanded to a larger sample size and properly peer-reviewed, from their very foundations, they are designed to tell us more about the specific context of essay writing than about overall cognitive capacity. And people are taking them as evidence for the latter in an increasingly unnerving way.

Generational Anxiety

That second point is the one I think is worth discussing, cause it's been following us for a long time, and we keep coming back to it like some weird cultural compulsion.

How is it that our current society simultaneously believes we're at the peak of innovation and industry, while also being convinced we're dumber than every previous generation?

It's become a meme at this point that every generation likes to say the younger one is lacking some fundamental aspect of life, which, of course, they themselves had in abundance.

Boomers say Millennials lack chutzpah, while the Silent Generation says Boomers lack a backbone. And, of course, we Millennials love to point out that Gen Z and Alpha will never know the pleasure of playing outside and enjoying a non-online world.

Isn't that silly? Taking a step back, it’s clear we're dealing with something other than actual cognitive decline if everyone’s been saying it forever.

My personal opinion is, there are only two measurable things that actually do impact a generation's mental acumen: socialization and nutrition. And that’s cause we’ve seen how societies change and become stronger when these two core necessities are met; while the reverse is also true.

That's about it. Even chemical exposure like lead paint or microplastics, which do affect individual capabilities, can't have generation-spanning effects on a society's intellect. If that were the case, we'd never have gotten the single greatest societal shift in the 20th century, because everyone would've been dumbed down thanks to factories, smog, arsenic, morphine and the million other things people were unwittingly (and sometimes, eagerly) putting into their bodies in the 18th and 19th centuries.

So yeah, I'm getting tired of the millionth anxiety-inducing headline telling me I'm getting dumber because I'm using Claude to fill in a spreadsheet. The truth is, human intellect is overall pretty much a constant. What changes is how we apply it to meet our society. And that’s the part that is changing significantly.

Are We Getting Smarter, Then?

If all of that innovation isn't making us dumber, and yet we keep accelerating technologically and culturally, what's actually happening? Aren't we making humans smarter in some ways?

I can't speak definitively to what LLMs are directly doing to our mental capacity, but following what has been studied and analyzed from the internet, mass media consumption, and literacy, I could take a gander and say that we are getting smarter, and we aren't at the same time.

Wade Davis, one of my favorite writers of all time, has explored the idea of an Ethnosphere. In his book "The Wayfinders," he elaborates on the concept of different, yet equally valuable, ways different peoples of the world have developed different abilities, and shaped their own reality through those abilities.

Davis defines the ethnosphere as:

"The sum total of all thoughts, dreams, ideas, intuitions, myths and memories brought into being by the human imagination since the dawn of consciousness."

It's his way of pointing out that just as we worry about biodiversity loss, we should be equally concerned about the erosion of cultural and cognitive diversity. His work is the most poignant example of how human intelligence isn't fixed.

The book’s namesake, the Polynesian wayfinders, really took me for a spin when I first found out about them. These navigators developed what's called a "star compass": a mental construct that divides the visual horizon into 32 houses, each separated by 11.25 degrees of arc. To them, water currents and the flow of waves are like highways, complete with proper signaling and entries and exits. They learned to visualize themselves as a constant point in the world, with everything else around them moving towards their destination.

It's hard even to grasp how they see the world, being so used to seeing myself as a dot in Google Maps. But that's the point, their brains developed extraordinary spatial and memory capabilities that most of us can barely comprehend because of their unique circumstances.

I've also been impressed by the sheer memory power of the ancient Greeks and any civilization with an oral tradition. No one knows how old the Iliad and Odyssey truly are, because by the time they were written down, they had already been sung by rhapsodians for potentially thousands of years.

Even the Bible survived thanks to the extraordinary ability of Dominican and Franciscan monks to reverse engineer the Hellenic Greek texts, without a translator, might I add, to such a degree of precision that when the Dead Sea Scrolls were found in the 1900s, the copies of the Bible translated by them, and the source text, were almost a 1-1 match.

These are but a few examples of extreme feats of human intellect, as well as the remarkable plasticity of the human brain. In the end, the abilities we nurture are the faculties we develop.

That's what I think is happening now with our measured “decline” in brain capacity. While LLMs, social media, and the internet are changing how we develop our brains, that doesn't mean we're getting dumber. It's just a symptom of a changing society. We're valuing certain types of skills more than others, and our brains are adapting accordingly.

Right now, memorization may be disappearing with the aid of computers, but that doesn't mean we're not developing other types of abilities like critical thinking, asking the right questions, and understanding core needs (because the execution of solutions is increasingly becoming immediate and cheap).

Our ability to execute on a plan is leaning more towards all of us becoming project managers instead of doing every task ourselves, and that has been happening even before LLM agents came along.

Just look at the gig economy and the rise of freelance work to see how we've been outsourcing the ability to complete tasks without our direct involvement. The global freelance market is growing at a compound annual rate of 15%, with freelancers contributing $1.35 trillion to the US economy in 2022 alone. By 2027, half of all US workers are expected to be involved in the freelance economy.

And yes, this means we have less context on the nitty-gritty details, as the Kosmyna and Hauptmann paper found, but it also means we've realized that it's the big picture that matters most to our current society.

As I wrote in my previous piece, "Asemica," language is changing thanks to online culture. Our literacy rates and ability to express complex thoughts through traditional writing may be on the decline, but that doesn't mean we aren't grasping the core concepts: we're just expressing them differently, through short-form content and memes. The medium is evolving, but the message is still getting through.

The Intelligence we *are* Building.

While I'm all for doing things the old-fashioned way as an exercise in ownership and craft, I don't think these media-baiting studies are doing anyone any good.

I'd like to see more research done on what kind of new faculties we're developing thanks to new technologies, instead of constantly looking at what isn't fitting with the current system anymore.

To me, we're not getting dumber. We're getting different. And we probably always will (bar Isaac Asimov’s “The Last Question” becoming a reality.)

The Polynesian wayfinders didn't become worse navigators when they started using stick charts to map ocean swells. The ancient Greeks didn't lose their storytelling abilities when they started writing things down (any Aristotle or Plato fans around?). And we're not losing our intelligence when we start using LLMs to handle routine cognitive tasks.

When I use Claude to help me organize data or draft initial thoughts, I'm not outsourcing my brain; I'm using a tool to get to the interesting parts faster, that’s not a controversial thought to anyone.

I believe looking at the avenues for human growth is a much more productive endeavor than the constant doomsaying that only discourages people from adapting and learning how to use these tools in their own way.

The question isn't whether we're getting dumber or smarter. The question is: what kind of intelligence are we building, and how do we make sure it serves us well?

I’m not good at outro text. Leave a comment if you agree, send hate if you don’t; let’s just chat about this, that’s the whole point.

The question isn't whether we're getting dumber or smarter. The question is: what kind of intelligence are we building, and how do we make sure it serves us well?

I think this framing is most important of all. Our unique capacity as a species is our plasticity, the fundamental ability to reprioritize cognitive load to better align with survival need and cultural demand.

In a new epoch of intellectual demand - it is prudent to approach this question in a way that seeks to understand what is necessary and what is prudent to keep within the domain of "human cognition" and what is perfectly appropriate to offload.

In this approach we can (hopefully) effectively categorize and develop clear metrics with which we can monitor our positive development WITH the technology holistically.

Enjoyed the post!